The Most Venomous vs Poisonous vs Dangerous and Deadly Snakes?

This article is an attempt to clarify the difference between some of the often-used adjectives describing snakes not only in Thailand but across the globe.

We’ve all seen videos, “Top 10 Most Venomous Snakes in the World” or ‘in Asia’ or ‘in Thailand,” etc. A number of times I’ve labeled some of my videos like this to try to hit the vast numbers of searchers who are looking for videos on YouTube about these topics. For some reason, people get excited about the MOST venomous, poisonous, dangerous, and deadly snakes and other animals in the world.

Poisonous Snakes

Let’s start with the easy one – poisonous snakes.

Poison refers to a substance’s ability to cause adverse effects in the human body by entering or touching the substance.

So, unless you’re eating the snake, it doesn’t matter whether a snake is poisonous at all. It could be the most poisonous snake on the planet, and it doesn’t matter if it bit you – unless it is venomous.

I’ve heard a number of times that the only poisonous snake¹ on the planet is Rhabdophis subminiatus – the red-necked keelback. The reason it is poisonous is because it frequently eats toads in the Bufo genus – which are highly poisonous. Bufo is a large genus of approximately 150 species.

These are true toads and part of the amphibian family, Bufonidae. Bufo is a Latin word for toad. In Thailand, we sometimes hear horrible stories about how entire families died after eating toads from this genus. R. subminiatus also secretes some of the toxins through its neck. So, you wouldn’t want to be licking this poisonous snake either!

I have yet to see anyone talking about another close relative of R. subminiatus being poisonous – the green keelback, as we call it here in Thailand, R. nigrocinctus. This snake probably has a similar diet as the red-necked keelback and would probably store the poison in the same way as its cousin in the same genus.

There is one more snake in the same genus here in Thailand, Rhabdophis chrysargos. Again, nobody is speaking about it being poisonous or venomous, but it could be both. Handle with extreme caution.

Eating very small snakes is not done so much in Thailand, so there may well be other poisonous snakes. It doesn’t pay to be the first to find a new venomous or poisonous snake under the wrong circumstances!

Venomous Snakes

OK, let’s tackle ‘venomous’ snakes.

A venomous snake is one which has venom and can inflict a bite or other wound into which that venom can be transferred.

There are a couple families of snakes in Thailand which are venomous. Elapids (Elapidae) and some Colubrids (Colubridae) have venom and can transfer it through biting or spraying in a stream to the eyes, as spitting cobras do.

Thailand Elapids include the true cobras (genus, Naja) and the King cobra, kraits, and coral snakes. These are front-fanged snakes that have fangs designed with a groove or hollow fang which transfers venom from venom glands in the upper jaw.

Thailand Colubrids include scores of snakes, some of which have enlarged rear fangs. It is more difficult for a Colubrid to get a good bite on most parts of a human to transfer venom, but it can be done. I have read studies recently that show many previously thought to be non-venomous snakes, are instead, venomous.

Meaning, they have venom. Some of them can work the venom into a wound by chewing repeatedly, causing tears in tissue with sharp teeth, whether they have fangs or not, and the venom can then act on the wound and produce envenomation.

Significant envenomation occurs when venom is transferred into the body through a wound and affects the body negatively.

Not all venom is the same, in fact, every venom from every species of snake is unique. Some venomous snakes like Chrysopelea ornata, the golden tree snake, have venom strong enough to stun a tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), but it has no effect at all on humans.

I’ve been bitten by this snake dozens of times and seen many other people bitten scores of times, and I’ve never seen an adverse reaction.

Some people call snakes that have venom which doesn’t affect humans significantly, ‘mildly venomous.’ It is a phrase that has stuck throughout the herping community, so I sometimes use it as well.

A snake which is mildly venomous could cause human envenomation, but it won’t lead to any lengthy hospital stay in most cases. I say most cases because there is always the threat of an adverse reaction to any venom which causes a person to go into anaphylaxis – and possibly anaphylactic shock, a potentially deadly situation.

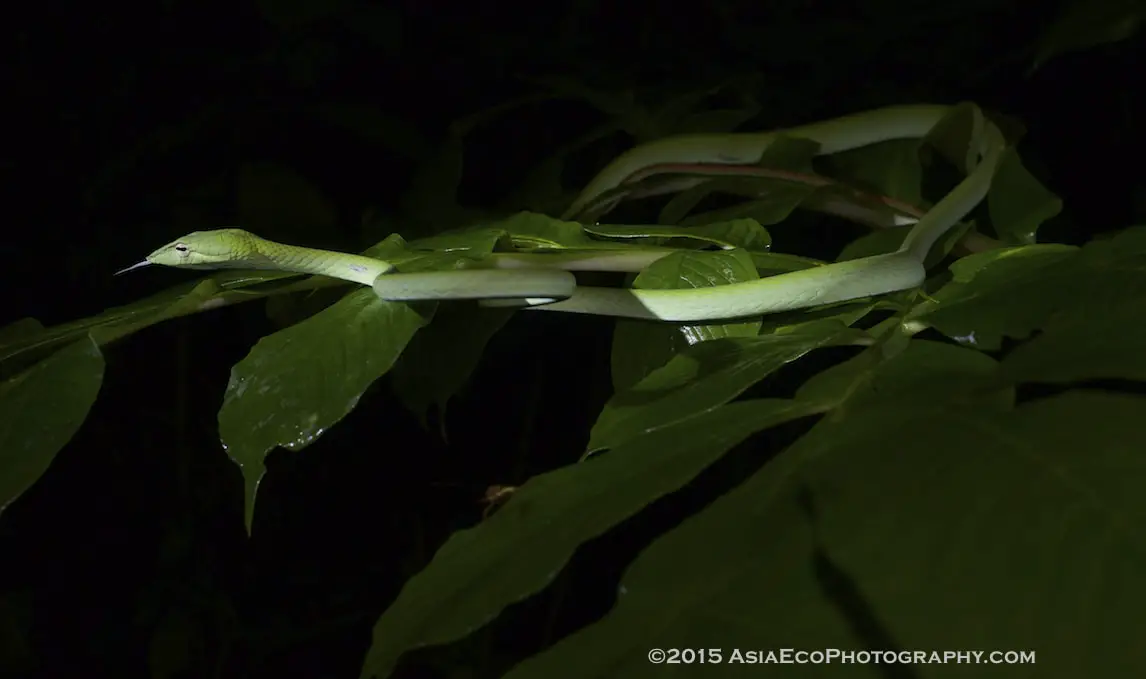

Some other mildly venomous snakes include Boiga dendrophila, Boiga nigriceps, Ahaetulla prasina, Ahaetulla mycterizans, and a few others that are not coming to mind.

Apparently, even rat snakes have a mild venom with some of the same venom compounds as king cobras. There isn’t sufficient concentration for significant envenomation to occur.

Scientists came up with another way to measure the strength of snake venom using a system that was already in place for evaluating the toxicity of pesticides on animals and generalized to people.

From EPA.gov: An LD50 is a standard measurement of acute toxicity that is stated in milligrams (mg) of venom per kilogram (kg) of body weight. An LD50 represents the individual dose required to kill 50 percent of a population of test animals (e.g., mice). Because LD50 values are standard measurements, it is possible to compare relative toxicities among venoms. The lower the LD50 dose, the more toxic the venom.

A venom with an LD50 value of .5 mg/kg is 10 times more toxic than a pesticide with an LD50 of 5 mg/kg.

For our purposes in the quote above, I replaced the word ‘pesticide’ with ‘venom’, and ‘rats, fish, mice, cockroaches’ with ‘mice.’

During a venom toxicity study, scientists will envenomate mice with venom from each snake and observe to see what quantity of venom it takes to kill half the mice. Ingenious, right? Not for the mice, but that’s another article!

So, because experimenting on live human beings, even with consent, wouldn’t be ethical, mice are used and contribute to our scientific understanding of just how dangerous, how potent the venom from some snakes is.

Now at first glance, this might look like a great way to ascertain how potent snake venom is. And in a way, it is. It’s definitely better than nothing. However, we’re talking about generalizing the ill-effect venom has on mice, to human beings. That is a big jump to make.

The results of LD50 studies are useful for comparing the potency of the venom of one snake against that of other snakes, but only in the case of envenomating mice, not people. Some venom has evolved to be more potent in killing mice than other venom.

Rhabdophis subminiatus, which isn’t known to eat mice, probably hasn’t evolved a venom specifically potent for killing mice. Calloselasma rhodostoma, the Malayan pit viper, eats primarily rodents. I’ve observed a mouse stop breathing almost instantly after being bitten by this snake.

The venom of some snakes is more lethal to mice than others. On the same line of thinking, the venom of some snakes is much more likely to cause significant and dangerous, even deadly, envenomation in humans.

That said, the LD50 scale is really all we have.

But, there are a couple more problems with the LD50 assessment.

The first is that there is not just one LD50 score for each snake. There are at least four. The reason there are up to four scores for each snake is because there are commonly four delivery methods for the venom, to cause closely-controlled envenomation in the lab of the test mice.

One test involves subcutaneous (under the skin) venom injection. Another is intravenous (into the vein). There is intra-muscular (into the muscle) injection, and finally, there is intra-peritoneal (into the abdomen) injection.

Each delivery method changes the LD50 score for each venom tested. I’ve never seen two LD50 scores the same for two different delivery methods.

The venom of some snakes has been tested again and again. King cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) venom, for instance. There are many studies that look at the venom potency of this, the largest venomous snake in the world because it is interesting and we know that the king cobra’s venom packs quite a punch since we know it can kill elephants and other large animals.

Some other snakes’ venom hasn’t been studied much, or even at all. You’d be hard-pressed to find a venom study of Ramphotyphlops braminus, the Brahminy blind snake. Why? It is one of the most common snakes in Thailand and across the globe, but the snake isn’t dangerous to humans, having neither a mouth to inflict a medically significant bite, or the venom to transfer if it did.

There are many snakes that have been insufficiently studied here in Thailand and across the world. The most common LD50 study is for subcutaneous injection because it is the easiest to set up and probably the most generalizable to human beings.

Still, it is a far cry from a realistic study on human effects. Many snakes are rated only for subcutaneous injection from what I’ve seen in studies.

Malayan pit vipers, any of the pit vipers really, and some of the elapids have very long fangs and inject venom deep within the tissue when they bite.

Is a subcutaneous LD50 test really relevant to showing the damage these snakes can do in mice or humans when they probably inject deep into muscle tissue during a typical envenomed bite?

No, of course not. But again, it’s all we have. The shortcomings of the LD50 scale are many. Let’s not even talk about the differences found in results between studies of the same snake species.

So, some people attempt to compare the dangerousness of snakes strictly by comparing their LD50 scores. Some compare across any of the delivery methods because they just don’t understand what they’re doing. They don’t know how to interpret the data in any kind of meaningful way.

Most people who are writing Top 10 Deadliest or Top 10 Most Venomous lists are just using the subcutaneous LD50 scores. This is really quite useless and misleading for a couple of reasons.

Not all snakes produce the same amount of venom. The king cobra, which, on a good day can express and inject about 7 milliliters of venom from its venom glands cannot be compared in any way to Rhabdophis subminiatus which probably cannot inject even one milliliter of venom into a mouse or human.

Still, on some subcutaneous LD50 charts (here’s one)², they show identical ratings of venom strength, .125 mg/kg.

Does it mean much at all that their venom is rated about the same in potency? Hardly. What really matters to people I think, in a real-life scenario, is the danger presented by envenomation from a certain snake.

This takes two things into account – the danger of envenomation by a particular snake when it does occur – because of the potency of the venom. And, the danger the snake presents – the temperament and proclivity and ability of the snake to bite and envenomate people.

Again as an example, R. subminiatus has an extremely potent venom. The thing is, it rarely bites, and when it does, it rarely envenomates – it bites and dashes away quickly. This snake needs seconds, tens of seconds it appears, to bite down and really transfer a significant quantity of venom.

This has only occurred a handful of times over the years. In fact, as most of you probably already know, until recently this snake was treated as a great non-venomous snake to have and handle. Now we treat it as a potentially deadly snake.

I’ve had emails and phone calls from people who have a relative in the intensive care unit with kidney failure as a result of bites from this snake! Amazingly, neither one died.

A king cobra has the means, the hardware (very efficient fangs), the potent venom, and the quantity of venom to kill a person very quickly with an envenomed bite. Luke Yeomans, a friend from the U.K., was bitten by an adult king cobra and died within minutes.

A young Thai man training to be a snake show presenter died in under ten minutes after a bite from an adult king cobra here in Krabi, Thailand. These are not snakes with venom in the top ten or twenty according to LD50 scales, but they are quite dangerous to mankind when cornered, surprised, or otherwise engaged.

So what I’m getting at is when you read a headline like, “Ten Most Venomous Snakes on the Planet!” or “Ten Most Deadly Snakes in the World!” You’ll have to take it with a grain of salt. Is the author speaking about venom potency in terms of subcutaneous or other LD50 scores? Quantities of venom produced? A number of people killed or bitten by that snake?

There really is no good way to compare snakes from different locations to come up with an inarguable list of the most deadly snakes in the world. Most of these lists look only at terrestrial (land-based) snakes. Some of the sea snakes have LD50 scores that show a much more potent venom than most terrestrial snakes.

For my own purposes, I do like to know where Thailand snakes rank in terms of LD50 subcutaneous and other methods of injection, but what is really important to me is a snake’s behavior and the likelihood it can bite me.

I try hard to avoid being bitten by any snake, not only because of the possibility of envenomation but because the possibility of causing harm to the snake when it does bite me also means a lot. Small snakes easily break teeth while biting humans, which they wouldn’t lose while biting frogs or geckos.

Anyway, just thought I’d write about this topic today and see if I could clarify my own thoughts on it.

If you have any comments, feel free to add them below.

Cheers!

Vern

1. Yikes. Even Dr. Bryan Fry, snake venom expert, says he was bitten by 26 ‘poisonous’ snakes at his VenomDoc.com homepage. Not sure why he uses that term. Maybe they were really poisonous and not venomous and he’s trying to make a point? No idea.

2. Just FYI – the venom chart shown conflicts with the chart results published by Dr. Bryan Fry some years ago, but which has subsequently been removed from his website. So, the veracity of the results displayed in this LD50 chart is not known.

Great post like always. Also, great site not only for herpers but for people like me especially living in Thailand and/or South East Asia who are not yet ready for herping but have an interest in snakes.

One question I have is if I was say, hiking and I come up on a King Cobra, if the King Cobra feels threatened by my presence and is upright hissing with its hood open, what should I do? Should I stay as still as possible pissing in my pants from fear and wait for the Cobra to make a retreat away from me, slowly walk away taking very slow steps back away from the Cobra, scream like a scared little girl and make a quick dash away from the Cobra, or put my hands to my mouth and make an imaginary flute with my fingers and start making flute noises? No but seriously, I really think this is an important question to address.

I was skimming and looking at your past posts but didnt see any information I needed on this question but the most I came up with was how to handle snakes which I KNOW would be the last thing I would try to do if I encounter a Cobra that feels threatened. If I missed a past post that you do have addressing this question, could you point me to that post?

Keep up the great job on the site!!!

Really tough question Jon! Brilliantly put, BTW.

It has been my experience that king cobras strike when there is movement away from them. So, if they’re standing close enough to strike, if you move back fast enough for them to register it – they may strike. Kings don’t usually strike when you’re absolutely still. I think if you are 2 meters away or more, you can just back up and get out of there. If any closer, be very careful about any movement at all. Eventually the king will probably start lowering the head a bit and will try to make a retreat.

Every situation is different. A king in a tree may act differently than those I’ve seen on the ground. A king in the water, may act quite differently. Hard to say!

Excreting into your pants may work as a diversion, not sure. Do let us know if you are in this situation and feel like sharing sometime!

Cheerz Brah!

Planning our trip to Thailand and like before spending a month in s.Africa and a month in Costa Rica , first thing I do is google ‘poisonous snakes’ of that country. In s.Africa we had to look hard for any snake, harder for venomous ones. Same in Costa Rica-it took forever to find a Fer De Lance and a long hike to find where an Eyelash Viper had been seen days prior; so I bet it will be the same in Thailand! Of course it doesn’t count to see one in a snake show :)

You have a really excellent website, much work and effort you’ve poured into it!

Thanks Robert! Yes, it can be difficult to find snakes in Thailand. I’d advise looking at the national parks at night with a Thai guide if you can find one. Cheers!